Cooking Up a Great Class: Seven Ingredients for Fun, Engaging Zoom Sessions

Whether you love it or hate it, or alternate between the two, teaching synchronously on Zoom might not be going away any time soon. Trust me, I know the struggle. The blank, silent squares. The awkward, enduring dead air. Our jokes dropping like radon balloons. The cricket-infested breakout rooms.

Yet, I also know that many of us have experienced amazing moments with our students on Zoom. We have seen excitement and deep engagement, risk taking, mistakes and growth, and the persistence and success of plate-spinning students who might not have been able to make the pieces fit without this option.

Online synchronous teaching also offers us a lot of exciting tools we can use to facilitate dynamic, relevant learning experiences. The world is changing for our students, as should the way in which we help them to thrive within it. There’s an opportunity to reestablish and emphasize the relevance of our disciplines within this context, but we must adapt.

I know most of us can still get down with some chalk or a squeaky pen on a white board and a classroom full of students, but it’s probably time we start folding into our practices some of the ubiquitous tech tools shaping the way people communicate, work, and live in 2022. Maybe our current crisis offers us the opportunity to learn ways to shake the habitual and situate the skill sets we hope to impart within the contours of the emerging information landscape and its digital toolbox?

7 Ingredients for Fun, Engaging Zoom Sessions

Although there isn’t a standard recipe, we can all find unique ways to slip some of the following ingredients into the instructional designs we cook up with our students.

- Start with thought and expression: get students engaged in a conversation, showcasing and affirming their interests and experiences before scaffolding in skill sets. I’ve learned from students that in my discipline, spending the first three weeks of the semester drilling MLA or sentence and paragraph structure before students are engaged in any meaningful conversations invariably leads to disenchantment with the class. Writing becomes a test, a hoop to jump through rather than a vital asset in their lives. Students have a lot to say and a desire for a forum. This is an asset that we should consistently leverage from day one. Give them a reason to want to further develop the skill or understanding each session hopes to impart, then drop just-in-time instruction in as needed. Long story short: contextualize the learning and try to have fun with it.

- Give them something to play with; make the experience durable: I love collaborating at meetings and conferences with colleagues and newly-met friends, writing interesting thoughts on whiteboards or gigantic sticky notes. It’s a great exercise for collaborative brainstorming and often sparks deeply-textured conversations–though, without fail, in my personal experience, this is cut short by time constraints and the facilitators’ itinerary. Yet, even though I have captured many of these scribbled notes with the camera on my mobile device, I literally never ever look back on these images or these ideas. They are buried in the ephemera of an ever-expanding cloud of data smog. The desire for something more durable is one of the potential benefits of synchronously learning together online (though this can and probably should be accomplished when learning in person, as well).

When we invite students to contribute to shared online documents, they become co-creators of resources shared by the entire class. Designing activities that ask students to collaboratively make or do something creative allows them to process the concepts or practice the skills together with a sense of accountability to one another and the course. They can learn from their colleagues’ examples. Offering opportunities for personalization and creativity allows them to infuse these creations with their brilliance. Designing activities which ask them to connect those concepts and skills to interests, thoughts, experiences, and expertise that they already have makes this learning even stickier.

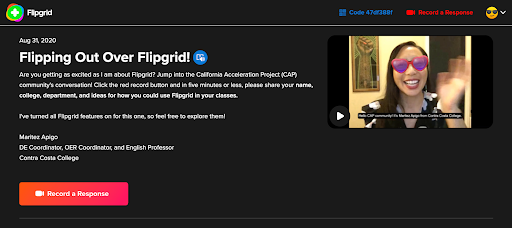

What’s more, students unable to attend a session can “make up” a missed class and share in the experience when we point them to these cataloged activities. These could be Perusall assignments, collaborative creative work created and shared with Google Slides, Padlet discussions, Google Jamboards, etc. Whatever the case, frame this collection of low stakes collaborative processing work as documentation of the oral history of your class. Emphasize the continuity and community of thought, growth, and imaginary it represents. Encourage them to use this resource as they work on more formal individual assignments. Here’s an example of an interactive Google Slide deck I created for students to collaborate around a few years back.

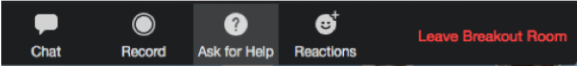

- Many paths; don’t be too rigid with how students can participate or earn points: students are going to get confused. Not everyone is working from the same space or has access to the same tools or expertise. Sometimes their browser settings block links you share or the tools you are asking them to engage with. Cortisol can quickly rise and learning will stop, especially if we show frustration.

Just talk it through with the student. Tell them not to stress out and offer suggestions for getting around these challenges. Offer them alternatives to the precise instructions you have given. Encourage and applaud resilience and “finding a way” in the face of roadblocks and let them know that this is essentially the key to success in college: taking a breath, asking for help when you can, and figuring it out.

For example, in the sample set of activities shared above, some students have had trouble writing on the shared slides. Here’s a few ways they could meaningfully participate that I might suggest: be the editor and fact checker; use the chat and ask your partners to copy/paste your contributions on the slide for you; find images for the collages and share the links; work with your team so that you contribute your voice to the shared project; keep talking.

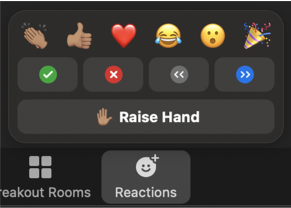

Beyond that, constantly remind your students of the many paths toward participation in the larger class discussions, outside of breakout groups. Some students flat out don’t want to talk in class. We should honor this introspection while finding ways to help these students share. I was in my second year of graduate school before I felt comfortable speaking in class without being forced to–being vulnerable and sharing stuff like that from our own journeys and growth can help too. Remind students to use the chat as a backchannel space to share and ask questions, but also engage with it yourself. Whether it's a comment, a question, an emoji, or an image, let students share what they want. Mention them by name and react positively to this engagement. It will catch on. Ask them a follow up question and use your judgment. Give them time, but if they aren’t feeling it, just move on casually. No big deal.

- Again . . . give them time! Honor the pause! It can be awkward, but when we are learning new things, we need time to think and process. Obviously, students are no different. Exercise your resilience to sit in the silence. I personally need to continue to work on this.

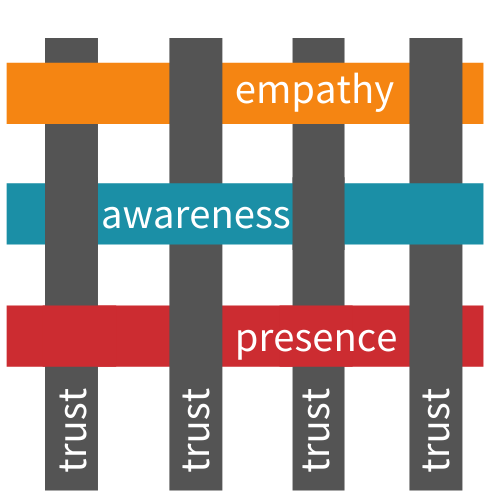

- Don’t coerce or surveille; entice and encourage: students need to feel seen and honored, not policed. Giving them a chance to share their strengths before asking them to develop skills they need to improve with is a great way to do this. In terms of learning on Zoom, remind them that leadership and collaboration aren’t mutually exclusive concepts and that developing these arts in a virtual context is probably going to be increasingly valuable in the years to come. Contextualize Zoom collaboration. Remind them that a college classroom should be a safe place where we support one another as we practice and take risks to grow in confidence. Remind them that the “real world” might not be as low stakes and everybody won’t always be on the same side, so it’s probably a good idea to build that confidence and those skills now. This is just one way to help students recognize that the intrinsic value of fully engaging far outweighs a collection of participation points and their impact on their final grade.

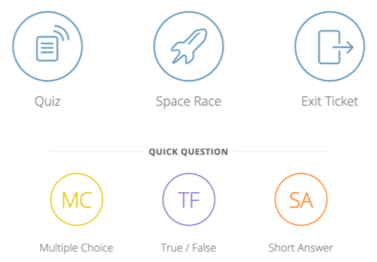

- Improve your digital literacy; practice with these tech tools: it’s really important to move smoothly from activity to activity. Mistakes will be made and we should use these as an opportunity to show ourselves grace and recover, but too many flubs can disjoint the class. Learning how to navigate effectively between different windows, documents, and Zoom tools is essential. This takes practice! I strongly suggest standardizing your practice and using dual monitors.

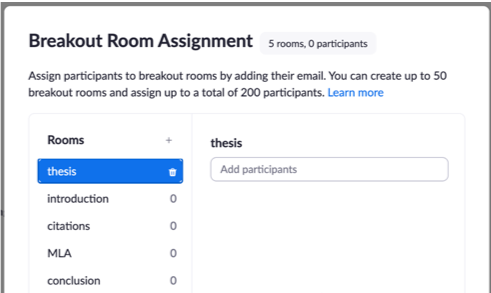

- Design human experiences with a flow; be strategic: one thing that really helps me with both points 5 and 6 is writing detailed itineraries that help me think through what I hope to accomplish with students, as well as providing a handy list of links I can quickly grab to drop into the chat for students to follow. Use down time effectively. Announcing that you are about to go into breakout rooms, then spending the next ninety seconds stressfully setting them up is not a good use of time. Same goes with sharing screens or links.

Rather, plan ahead by carefully considering the flow of your session. For example, set up breakout groups while students are journaling and take attendance or make on-the-fly adjustments to activities while they’re in breakout groups. You are designing and facilitating a set of experiences, so consider transitions from the students’ perspective. Rhetorical awareness is essential. What are you going for? What do you want students to get out of the session? What are the best designs to accomplish this? Finally, things won’t always go as planned. If your awesome designs that you worked very hard on aren’t landing, give yourself and your students a break. It happens! Don’t force it. Afterwards, reflect and adjust.

In the end, the best piece of advice I can give is that we should adjust our attitudes. If we aren’t excited by these modalities or if we criticize learning online this way, our students will follow suit. Our energy interacts with students in a feedback loop. They tend to mirror our vibe and we theirs. If we are excited, there’s a better chance they will be too . . . which then intensifies our own excitement and so on. The same is true if we are frustrated and annoyed. Whether it’s this or the lens by which we see our students, either as a collection of deficits or a collection of assets, the mindsets and energy we bring to our classrooms–virtual or not–can be prophetic in a self-fulfilling kind of way.

Setting the tone starts with us having faith in our students’ capacity and recognizing that teaching through Zoom isn’t just a shoddy stand-in for “real teaching”; it is vibrant and increasingly vital. It’s a space where our students can thrive and where we have a chance to innovate in creative ways.

Learn with me!

Join me on March 9, 2022 at 1:00 PT for a free online workshop, Simple Teaching Strategies for Fun, Community-rich Zoom Classes. Register for free now. See you there!