How and why to humanize your online course

by Michelle Pacansky-Brock

What is humanizing?

Humanizing applies learning science and culturally responsive teaching to asynchronous online courses to create an inclusive, equitable class climate for today's diverse students. When you teach online, it is easy to relate to your students simply as names on a screen. But your students are much more than that. They are capable, resilient humans who bring an array of perspectives and knowledge to your class. They also bring life experiences shaped by racism, poverty, and social marginalization. In humanized online courses, positive instructor-student relationships are prioritized and serve "as the connective tissue between students, engagement, and rigor" (Pacansky-Brock et al., 2020, p. 2). In any learning modality, human connection is the antidote for the emotional disruption that prevents many students from performing to their full potential and in online courses, creating that connection is even more important.

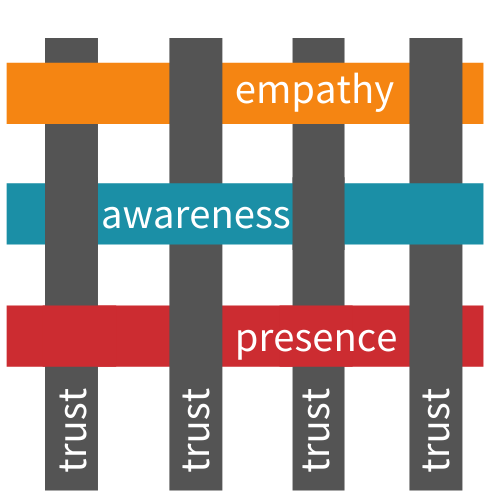

The Principles

Humanized online teaching is supported by four interwoven principles:

- Trust: As an instructor, it is your responsibility to intentionally cultivate student trust, and one way to do it is by practicing “selective vulnerability” (Hammond, 2014) in the online community you build with your learners. Choose to share aspects of your life that portray you as a real person – tell a story about a personal struggle you worked through or record a video while cooking dinner or walking your dog.

- Presence involves intentional efforts to construct your authentic self through brief, imperfect videos to ensure your students know you are in this journey with them (Costa, 2020). Verbal and nonverbal cues add context to your communications, which is important to support culturally diverse students.

- Awareness is achieved by learning about who your students are and how you can support them.

- Empathy requires you to slow down, see things through your students' eyes without judgment, be flexible, and support them towards their goals.

The Pedagogy

"Students who often feel invisible and unimportant" – they need to be 'seen' and valued by educators. (Wood & Harris III, 2017, p. 41)

Research on men of color and first-generation students in community colleges has emphasized that "relationships before pedagogy" is a tenet of effective teaching (Palacios & Wood, 2015; Rendón, 1994; Wood & Harris III, 2015). Yet, when community college students learn online, they are less likely to experience rapport with their instructor and more likely to report needing to teach themselves (Jaggars & Xu, 2016). The lack of instructor-student relationships in many online courses exacerbates equity gaps. Humanizing intentionally cultivates a "welcomeness to engage" through trust, mutual respect, and authentic care (Wood & Harris III, 2015) before moving on to course content. Positive instructor-student relationships are leveraged to hold students to high standards, validate their effort and ability, and support them with achieving their goals. Students are more likely to lean in and apply themselves at a higher level when they know their instructor believes in them (Gay, 2000; Hammond, 2015; Ladson-Billings, 1994) and the same principles hold true in online courses (Glazier, 2016).

Mitigating the Impact of Stereotypes on Learning

Humanizing intentionally creates a learning environment in which everyone is welcomed, supported, and recognized as capable of achieving their full potential. This requires a commitment to becoming continuously aware of your unconscious bias and flattening the hierarchical structure of power embedded in White dominant culture. Instructors of humanized online courses recognize that students from non-majority groups are more likely to experience belongingness uncertainty (Walton & Cohen, 2007) and stereotype threat (Shapiro et al., 2016; Steele & Aronson, 1995). These phenomena disrupt the emotional conduits that steer cognition and, in turn, prevent students from performing at their best. Human connection allows students to feel safe by mitigating the psychological impact of stereotypes. With freed up cognitive resources (Vershelden, 2017), more students enter the Zone of Proximal Development where learning takes place (Vygotsky, 1978).

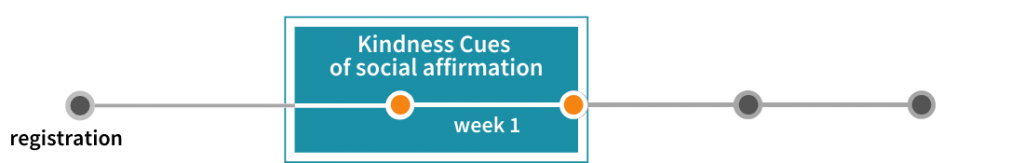

High Opportunity Zones

Weeks 0-1

Feelings of social isolation can worsen when students learn at a distance from their peers and instructor. To lower this barrier, humanized online courses incorporate kindness cues of social inclusion (Estrada et al, 2018.) into the “high opportunity zone” of an online course – the week prior to the start of instruction and the first week of a class.

STEM

The culture of STEM education offers a microcosm of inequity. Black, Latinx, and Indigenous students leave STEM fields at greater rates than their White peers, and this problem is worse in STEM than other discipline clusters (Riegle-Crumb et al., 2019). Traditional, deficit-based instructional paradigms have created a "weed out" culture in undergraduate STEM courses. An overwhelming majority of students who switch out of STEM majors cite poor teaching (96%) and competitive course climate (81%) as problems that contributed to their decision (Seymour & Hunter, 2019). Humanizing online STEM courses is not a fix for every problem in STEM, but it is a start to creating more inclusive learning environments that will also expand opportunities for students who do not have the privilege to be on campus.

The 8 Elements

Teaching is a practice of continuous improvement. When we teach online, we may have a clear sense of the type of experience we want to cultivate for our students, but we may lack clear, practical steps to get there. The eight humanizing elements suggested below are offered as starting points for you. Try them. Adapt them. Make them your own and observe the results in your students' engagement and performance.

Liquid Syllabus

“I will be a partner in your learning.”

Humanize your pre-course student contact by creating a public, mobile-friendly website that contains a brief, imperfect welcome video; a learning pact detailing what your students can expect from you and what you'll expect of them; a teaching philosophy that conveys diversity as a value; tips for success; week one due dates and required materials; and a link to log into your course. Email the link to your Liquid Syllabus to your students the week prior to the start of instruction so they feel welcomed and prepared for a successful start. Save the policies, procedures, and other details for the course syllabus; with your liquid syllabus, convey a warm, welcoming first impression of you and your course.

Humanized Homepage

“You are welcome here.”

Ensure your students are greeted with a clear, friendly homepage when they arrive in your course. Include a visual banner; a brief video that welcomes and tells them how to proceed; and a clear "start here" button that links to the first module.

Getting to Know You Survey

“I want to know how to support you.”

In week one, have your students complete a confidential survey that provides you with microdata about their individualized needs. Be sure students understand it is for your eyes only and that you will support them throughout the course with what they choose to share.

Warm, Wise Feedback

“I believe in you.”

Your feedback is critical to your students' continuous growth. But how you deliver your feedback really makes a difference, especially in an online course. To support your students' continued development and mitigate the effects of social threats, follow the Wise feedback model (Cohen & Steele, 2002) that also supports growth mindset (Dweck, 2007). Deliver your message in voice or video to include verbal and nonverbal cues and minimize misinterpretation. In your feedback, include:

- A reminder of high standards ("this is a tough problem") so students are cued that mistakes are reflective of the course's rigor, as opposed to their abilities.

- A personal assurance that informs the student they are capable and will improve with effort ("Look how much you've improved already, keep going. You've got this.").

- Specific actionable steps to work on ("Next, I want you to work on ...").

Self-affirming Ice Breaker

“Your values and experiences matter.”

Anxieties are highest in week one. To remedy this, invite students to participate in a low-stakes ice breaker that encourages sharing about something important to them. This real-world connection reduces stress, prepares them to engage in course content, and enables them to discover shared interests with their peers. Example prompts: Share a photograph of something important to you and discuss why you chose it; if you could only keep two items with you for the next month, what would they be and why; share your goals and aspirations with us. Use an asynchronous voice or video tool for an added humanizing kick!

Wisdom Wall

“Learning is a process of growth.”

Exposing students to role models with like identities increases self-confidence and minimizes stereotype threat (Steele & Aronson, 1995) by changing the narratives students lean on to anticipate their challenges (Spitzer & Aronson, 2017). And engaging students in metacognition helps them to recognize their learning progress, increasing self-efficacy. Create a Wisdom Wall (Pacansky-Brock, 2017) at the end of a course by asking students to reflect back to the start of the course and identify something they know now that they wish they had known then. Then ask them to share that idea in the form of advice for your next group of incoming students. When your next course begins, share the Wisdom Wall with them in week one.

Bumper Video

“I am here to help you learn.”

A bumper video is a 2-3 minute, visually-oriented clip that includes background theme music and is designed to introduce a new module or clarify a sticky concept. Sprinkle bumper videos throughout your online course to differentiate your students' learning and empower them to quickly and independently revisit key concepts and ideas.

Microlectures

“I am here to help you learn.”

Create a series of short (5-10 minute), laser-focused videos to guide your students through the comprehension of complex concepts. Before you record, identify one or two things you want your students to take away from the video. At the start of the video, tell your students what they will learn.

References

Asai, J. A. (2020). Race matters. Cell (181), 754-757.

Cohen, G. L., & Steele, C. M. (2002). A barrier of mistrust: How stereotypes affect cross-race mentoring. In J. Aronson (Ed.), Improving academic achievement: Impact of psychological factors on education (pp. 205-331). Academic Press.

Costa, K. (2020). 99 tips for creating simple and sustainable educational videos: A guide for online teachers and flipped classes. Stylus.

Dweck, C. S. (2006). Mindset: The new psychology of success. Random House.

Estrada, M., Eroy-Reveles, A., & Matsui, J. (2018). The influence of affirming kindness and community on broadening participation in STEM career pathways. Social issues and policy review, 12(1), 258–297.

Eyler, J. (2018.) How humans learn. West Virginia Press.

Gay, G. (2000). Culturally responsive teaching: Theory, research, and practice. Teachers College Press.

Glazier, R. A. (2021). Connecting in the online classroom: Teachers, students, and building rapport in online learning. Johns Hopkins University Press.

Hammond, Z. L. (2015). Culturally responsive teaching and the brain: Promoting authentic engagement and rigor among culturally and linguistically diverse students. Corwin Publishers.

Immordino-Yang, M. H. (2016). Emotions, learning, and the brain: Exploring the educational implications of affective neuroscience. W.W. Norton & Company.

Jaggars, S. S. & Xu, D. (2016). How do online course design features influence student performance? Computers & Education, (95), 270-284.

Kleinfeld, J. (1975). Effective teachers of Eskimo and Indian students. School Review, 83, 301–344.

Ladson-Billings, G. (1994). The dreamkeepers: Successful teachers of African-American children. Jossey Bass.

National Research Council, (2000). How people learn: Brain, mind, experience, and school: Expanded edition. The National Academies Press.

Noddings, N. (2013). Caring: A Relational Approach to Ethics and Moral Education, 2nd ed. University of California Press.

Palacios, A. & Wood, J. L. (2015). Is online learning the silver bullet for men of color? An institutional-level analysis of the California Community College system. Community College Journal of Research and Practice, 40(8), 1-13.

Pacansky-Brock, M. (2017). Best practices for teaching with emerging technologies (2nd ed.). Routledge.

Pacansky-Brock, M. (2014, August 13). The liquid syllabus: Are you ready? [blog post]. https://brocansky.com/2014/08/the-liquid-syllabus-are-you-ready.html

Rendón, L. (1994). Validating culturally diverse students: Toward a new model of learning and student development. Innovative Higher Education, 19, 33-51.

Riegle-Crumb, C., King, B., and Irizarry, Y. (2019). Does STEM stand out? Examining racial/ethnic gaps in persistence across postsecondary fields. Educ. Res. (48), 133-144.

Shapiro, J., Aronson, J., & McGlone, M. S. (2016). Stereotype threat. In T. D. Nelson (Ed.), Handbook of prejudice, stereotyping, and discrimination (p. 87–105). Psychology Press.

Spitzer, B. and Aronson, J. (2015). Minding and mending the gap: Social psychological interventions to reduce educational disparities. The British Psychological Society, 85, 1-18.

Seymour, E. and Hunter, A.-B., Editors. (2019) .Talking about leaving revisited: Persistence, relocation, and loss in undergraduate STEM education. Springer Nature.

Steele, C. M., & Aronson, J. (1995). Stereotype threat and intellectual test performance of African Americans. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 69, 797-811.

Vershelden, C. (2017). Bandwidth recovery: Helping students reclaim cognitive resources lost to poverty, racism, and social marginalization. Stylus & AACU.

Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes. Harvard University Press.

Wood, J. L., Harris, F. III, & White, K. (2015). Teaching men of color in the community college: A guidebook. Lawndale Hill.

Wood, J. L., Harris, F. III. (2017). Supporting men of color in the community college: A guidebook. Lawndale Hill.

Wood, J. L. (2019). Black minds matter: Realizing the brilliance, dignity, and morality of black males in education. Montezuma Publishing.

Recommended citation:

Pacansky-Brock, M. (2020). How to humanize your online class, version 2.0 [Infographic]. https://brocansky.com/humanizing/infographic2

This resource was created with funds from the California Education Learning Lab and is shared with a CC-BY-NC license.